At a recent event hosted by the Dartmouth Quant Club, I was introduced to the dynamic world of quantitative finance. Within the broader financial ecosystem (which encompasses traditional investment banks, hedge funds, and asset managers, among others) lies the unique position of market makers. But what exactly is a market maker? And, perhaps more important, what role do they play in the financial ecosystem?

You might have heard of some of these firms before: Jane Street, SIG, Optiver, Citadel Securities—these are some of the most prominent market makers in the world. Most operate as proprietary trading houses (that is, they risk their own money to make profits) and their trading volumes are huge: Jane Street reportedly moved over $17 trillion worth of securities in 2020 [1].

But what exactly do they do? What is “market making”? In the simplest terms, market makers provide liquidity to the market. That just means that they are on standby to buy or sell securities at publicly quoted prices (in fact, they are obligated to do so) [2]. For each security (this could be a stock, an ETF, etc.), a market maker posts two prices: a bid price (the price at which they are willing to buy stock from you) and an ask price (also called the sell price, i.e., the price they are willing to sell stock to you). This ensures that there is always someone on the other side of a trade.

Let me explain: Imagine you want to sell your Tesla stock right now. Without a buyer immediately available, you would have to wait. Or, even worse, drop your price to attract one. Market makers solve this problem by always being ready to buy from you (at the bid price) or sell to you (at the ask price). They “make the market” by publicly posting both prices at all times, so trades can happen instantly. This keeps markets liquid, smooth, and efficient, which is especially needed in times of crisis.

But how do market makers make money then? In essence, they profit from something called the spread—the small difference between the price at which they buy (bid) and sell (ask). To illustrate this more intuitively, I will provide a simple example below.

Say Jane Street is market-making a stock priced around $100.

Bid: $99.95: they will buy from you at this price

Ask: $100.05: they will sell to you at this price

The spread therefore is $0.10. Now imagine the following situation:

A trader sells 1 share to Jane Street at $99.95

Another trader buys 1 share from Jane Street at $100.05

Jane Street will therefore buy one stock for $99.95, and sell one stock for $100.05. So they just made $0.10, and still end up having the same exact number of stocks as before. Now imagine doing that a million times, and you have yourself $100,000. Essentially, that is how market makers make money.

But why set the spread at just $0.10? Why not more, or less? This is called the wide market/tight market tradeoff. A large spread is called a “wide market”. Market makers can potentially earn more per trade, but these markets often have lower trading volume or less competition. A small spread is a “tight market”. There is less profit per trade, but high volume and competition can make up for it. Tight markets are usually more efficient and liquid. However, any market will always depend on two things.

First, a good fair price estimate, and second, an information advantage. A good fair price estimate is just an educated guess of what the asset is worth right now. And it is permanently updated as trades and market info come in. There is no single “fair” price, just the price you're willing to trade at, based on risk, volatility, and expected movement. If your quoted bid/ask is far from this evolving “true” value, you risk being picked off by traders who know more or move faster. This has to do with the information advantage.

Broadly speaking, knowledge is power. If you can react faster than others to news, order flow, or other subtle patterns in the data, you can use this new information to update your position. The goal isn't just to trade per se. Rather, the goal is to trade when others don’t yet realize the price has changed, because this is when the biggest gains can be made.

As a consequence, the biggest danger to market makers is price movement between trades. As I will illustrate in the following example, things can go very wrong. Let’s say a market maker buys 1 share at $99.95, expecting to sell it at $100.05. But before a buyer appears, the stock price drops to $99.00. Now, they are holding a share they bought for $99.95, but can only sell it for $99.00. Ergo, they lose $0.95. In technical terms, this is called inventory risk. The longer they hold the stock, the more exposed they are to price changes. But here too, market makers use strategies to hedge against this risk. There are two main strategies.

First, speed. Market makers try to buy and sell almost instantly, so they aren’t stuck holding the stock. Many trades happen in milliseconds, which is also why they use specialized hardware. This is the reason you see open FPGA positions at these firms; FPGAs are used in high-frequency trading (HFT) because they can be customized at the hardware level to perform specific tasks. This allows for ultra-low-latency execution and parsing of market data.

The second method is hedging with related assets. If they can’t sell the stock right away, a market maker might offset the risk. The idea is: if the stock’s price falls, their hedge gains value, offsetting the loss. Let’s say they just bought a major tech stock. To hedge against it, there are three common options:

Hedge by shorting an ETF that contains that tech stock.

Hedge by selling futures of that stock.

Hedge with options.

The latter especially is major. The Financial Times reported that Jane Street at a company level spends $50–$75 million a year on put options to cover in case the markets drop [1]. And that matters: market makers’ job is to keep markets running by always being willing to buy or sell. During the crash in March 2020, when bond markets were freezing up, ETFs still kept trading, mainly because Jane Street and similar firms were behind the scenes providing liquidity. Many experts say bond ETFs held up better than expected thanks to these market makers. Their influence has grown so significantly that some firms have now even been added to the Federal Reserve’s list of trusted counterparties during emergency bond-buying programs. Their ability to stabilize markets in moments of panic has made them systemically important to modern finance.

At its core, market making is about informed risk-taking and rapid decision-making under uncertainty. And unlike traditional investors who take directional positions, market makers rely on quantitative models to estimate fair value and manage their exposure. Essentially, they make money not by predicting where prices will go, but from how prices move around their quotes. In a way, it is a constant balancing act: providing liquidity, while not being caught on the wrong side of sudden market moves.

During the Quant Club meeting, we were essentially simulating this behavior by playing “Selling Suits”. The rules are given below.

Selling Suits – Market Making Game

Setup

Groups sit in a circle

Each group is given 2 cards

Suits & Values:

■ Diamonds = 5

■ Hearts = 10

■ Clubs = 15

■ Spades = 20

■ Jokers = 50

Gameplay

Objective: Make markets on the sum of everyone’s card scores

Market Width: Starts at 50

Trade or Tighten:

■ Everyone has the option to narrow (tighten) the current market width or pass

■ The player who posts the smallest range/width gets to set the market (their bid/ask price aka low to high range)

■ All other players decide to buy or sell at that set market price

■ Limited to buying/selling up to 3 shares per roundBetween Rounds:

■ Each player passes one card to the person on their rightEnd Game:

■ The game continues for a set number of rounds

■ Final Profit determines the winner

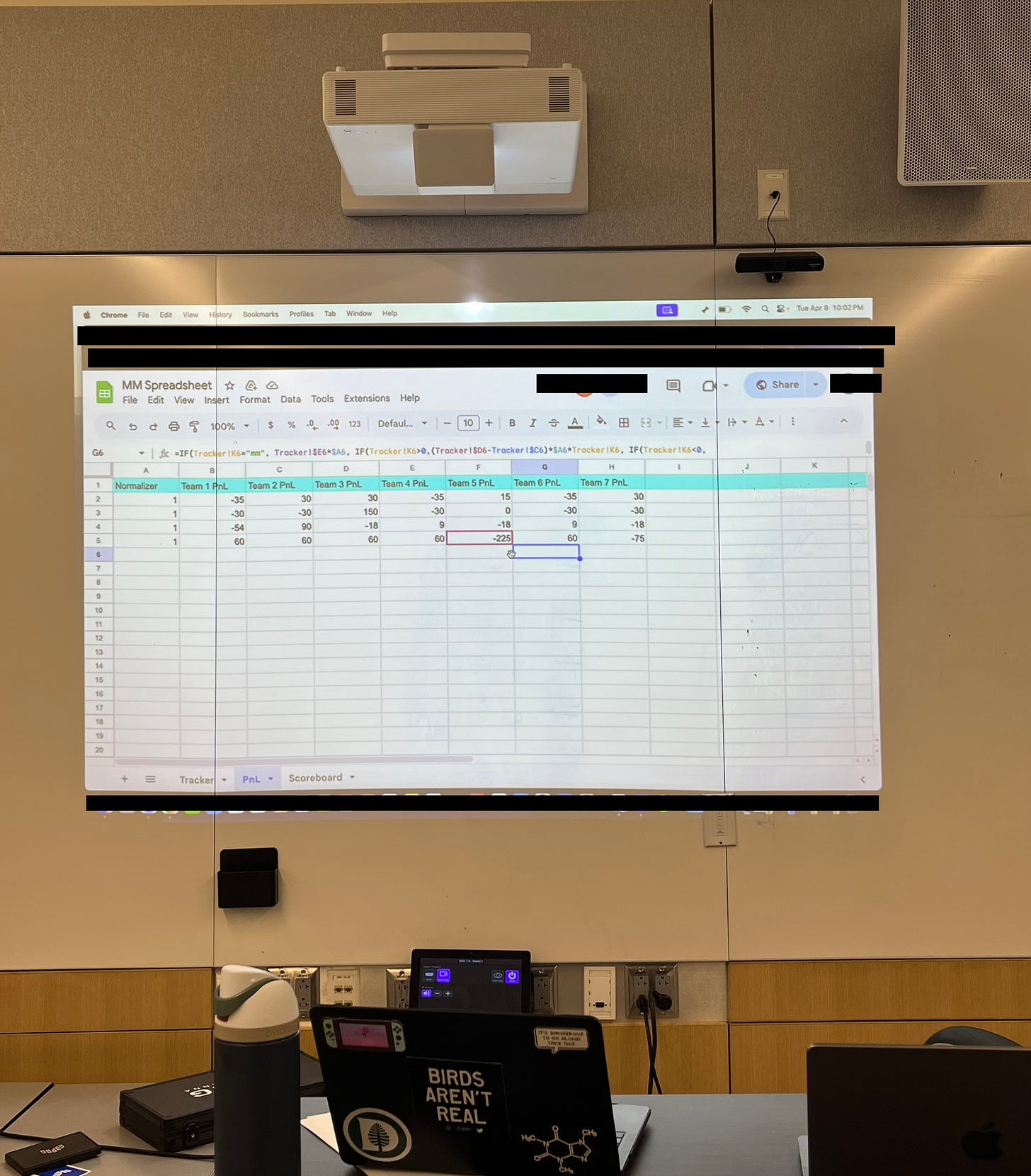

In this game, each group (there were 7 groups total) was dealt 3 cards from a standard playing deck. There were 21 cards overall in the game, and the objective was to estimate the total sum of points from all cards in the game (basically, estimate the expected value as well as possible). With each successive round, as people passed one of their cards to the next table, the amount of certainty per team increased because more of the cards that were in the game were revealed. At the start of each round, each team effectively had the chance to act as a market maker, setting a range in an attempt to profit from others' uncertainty about the hidden total. The tighter your spread, the more attractive your market. But simultaneously, the more risk you took on if your estimate was wrong. It was a very fun experience, and combined educated estimates with some bold moves. I highly recommend playing at your next (quant) party.

[1] Jane Street: the top Wall Street firm ‘no one’s heard of’

[2] Market Maker Definition: What It Means and How They Make Money